union church from 1853 to the present

Following the Demands of Impartial Love

“God has made of one blood all people of the earth.”

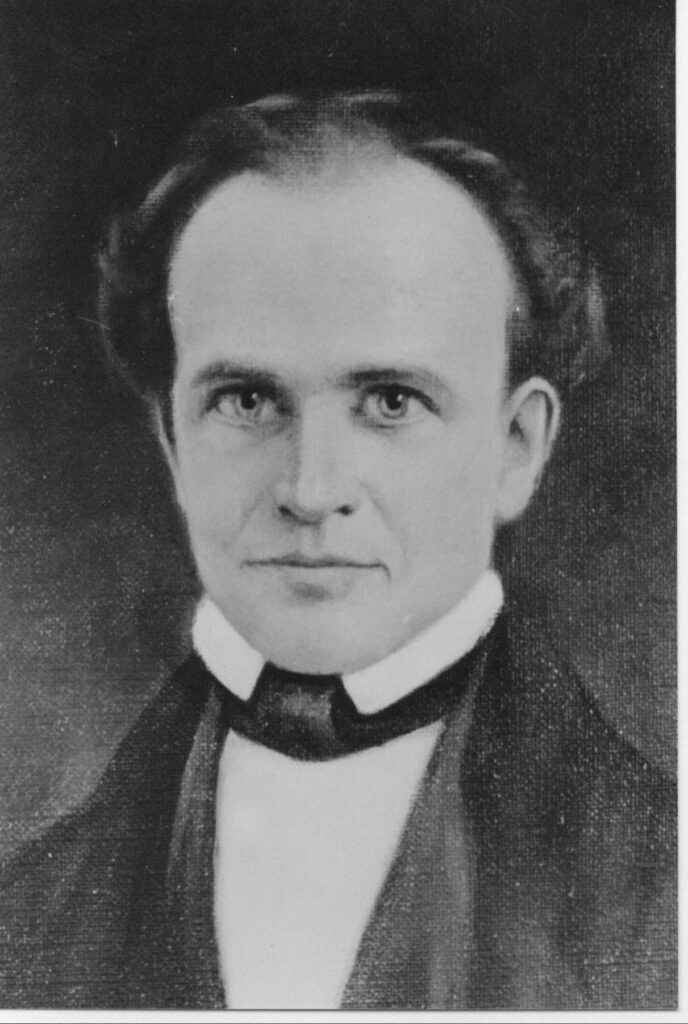

During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, Rev. John G. Fee, an ordained Presbyterian minister, had become grievously disaffected with his own denomination and many others for refusing to take a stand against enslaving people, for fear of losing members and revenue. He believed that there was a higher law than human legal codes, and that every church should practice God’s “impartial love.” Acts 17:26 became his motto as he preached throughout Kentucky during the 1840s and early 1850s:

This was not a popular opinion. Fee was run out of many towns on sight for his views. In 1853 he was invited to preach in Madison County by Cassius Clay, nephew of Henry Clay and owner of Whitehall estate. Clay was also an abolitionist and published many of Fee’s writings in his newspaper.

Fee preached just down the hill from the current hospital in Berea, and this time, he was not rejected by his audience. His welcome so encouraged him that he accepted Clay’s offer of ten acres of land if he would settle and found a church.

A New Church

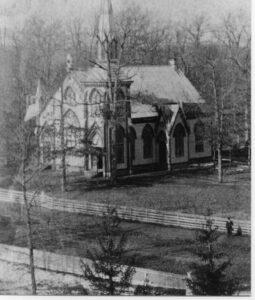

Fee did, and called the place “Berea” after the town in acts that Paul mentions as “having received the word of God with gladness.” Union Church immediately became an early outpost for abolition in an overwhelmingly slaveholding county. Two years later, in 1855, Fee and his co-workers founded Berea College on the same principles.

The small church built a log cabin near where Whitaker Bank now stands on the corner of present day Boone and Chestnut Street and worshiped there for several years. Fee called the church “The Church of Christ, Union,” (still the church’s legal name); the first part being a common 19th-century indication that this church was of no particular denomination, and “Union” signifying that all were welcome to this union of kindred minds. (The name proved even more providential when the Civil War broke out.) Because the members came from many traditions, it was decided that all forms of baptism would be recognized: sprinkling or immersion, and that each family or individual could discern for themselves which form was right for them. Slaveholders were not accepted as members, though the views of the church likely did not attract such families.

The church also adopted the Fellowship Principles at this time, which underscored loyalty only to God and Christ’s mission:

Rev. John G. Fee

The Church of Christ, Union, receives all followers of Christ and works with all who work with him, respecting each one’s conscience, working by love, endeavoring to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.

Union Church Fellowship Principles, 1853

This statement is still affirmed by all who join the congregation. Importantly, it emphasizes the responsibility for working together with respect for the conscience and diversity of membership. The only absolute was the demand of love on all people for all people.

Exile

Abolitionist views were still not only unpopular, but dangerous. In one letter, Fee lamented that there were too few men in the pews because they preferred to station themselves in the woods around the church to protect the women and children inside. Late in 1859, friends of the church rode to town to warn Rev. Fee and the deacons that a lynch mob had been assembled in Richmond and was headed south. Prominent members of the founding families packed hurriedly and fled town. All escaped and ultimately, aside from some vandalism, the mob dispersed, but it remained unsafe for Union Church members to return. They would be in exile for the next four years as conflicts in the Civil War crossed back and forth across the state, spending most of that time with relatives across the Ohio near Cincinnati.

Seeking Joy and Justice Together

At the conclusion of the war, Union Church members assisted in resettling thousands of freed slaves to Berea, many of whom had served in the Union Army and been mustered out at Camp Nelson to the west. According to Dr. Richard Drake’s history of Union Church, the Blacks called Berea “Freetown,” and this was when Fee began to truly succeed in creating his “practical, utopian ideas” [p. 15] of an integrated college and town, with Black and white families interspersed together, going to school and church and work together. Union Church partnered with groups like the American Missionary Association to bolster the number of teachers for Berea College, and it became the first college in the south to admit Black and white persons to the same classes. Women were also admitted, making Berea only the third co-educational school in the country.

At this time, there was little distinction made between the church and the college they had founded. Worship was a required part of the curriculum, and all faculty were also expected to teach a Sunday School class. In 1868, a new church was constructed (approximately where Frost Hall stands today) that served both student and town populations. In 1871, Union hired its first African American staff member to serve as an associate pastor, joining other faculty like J. A. R. Rogers, who took over the preaching whenever Fee went on a speaking or fundraising tour.

Another New Congregation

Rev. Fee continued to serve for 41 years, until his personal Bible study convinced him that only baptism by immersion was acceptable. He asked the church to revise its stance, but the congregation demurred. Ultimately, Fee tendered his resignation and founded a new congregation in the barn on the corner of his property, barely a block away. “Second Church of Christ, Union” eventually became the present-day First Christian Church, with whom Union Church has a long and friendly relationship.

Twentieth Century Segregation and the “Day Law“

The early part of the 20th century proved tumultuous for Union Church. Fee’s death in 1901 affected the entire town. In 1903, the church building burned to the ground from a faulty stove, and in 1904, the Kentucky Legislature passed the Day Law, specifically targeting Berea College and the church. The law forbade any institution from educating “different races” within 25 miles of each other. The church contested the law in the Supreme Court (closing its interracial Sunday Schools in the interim) but they lost the case.

Berea College divided its endowment in half, bought a 444-acre campus in Shelby County, some 40 miles away, built on it, and founded the Lincoln Institute, which educated people of color based on the Tuskegee pattern. Berea College and Union Church became all-white institutions. Job losses, especially for African Americans, depleted the population, and Berea’s proud tradition of a truly interracial society, small as it might be, seemed lost. But Bereans never lost sight of their mission, and never stopped working toward it.

A New Sanctuary

In 1922, after nearly 20 years of delays and the deprivations of World War I, Union Church finally completed their new sanctuary. During the wait, the church met in the Foundation School Chapel, a multipurpose room off a dormitory that sat on the site of the present-day Boone Tavern parking lot. This brick-and-limestone, neoclassical revival building (in which we still worship today) was celebrated as a grand anchor to College Square. It was built to seat 1100 persons, the entire population of Berea and students at that time. The congregation proper numbered about 325, but the congregation wanted both the sense and the practical use of a New England-style town meeting hall, and major gatherings still happen at the church. The building was modeled after First Congregational Church of Oberlin, Ohio, Oberlin being very much a sister institute with Berea at that time. To this day, the two sanctuaries share a great heritage in architecture and mission.

Together Again, Still Seeking Justice and Joy

Despite the drastic changes of two world wars and repressive social conditions, Union Church never lost its sense of mission, or the roots of its founding. The Day Law was finally repealed in 1950, and the college reintegrated and boldly took interracial sports teams to tournaments across the region. When the Civil Rights movement began to take shape, many Union Church members were on the front lines. We still have members at this writing who rode on Freedom Buses and marched in Selma.

Union Church youth group members organized and helped peacefully persuade local businesses to take down the “whites only” signs on their storefronts, public restrooms, and drinking fountains. Members of the church intervened when a black man defending himself killed his white assailant. They guarded the jail where he was kept so there would be no lynching, and helped raise funds for his legal defense.

In the late 1960s, Union Church and Berea College formally became separate entities, but remain partners in mission and outlook to this day. The college still provides world-class, tuition-free education to students of any ethnicity, from the Appalachian hill counties to citizens of dozens of countries across the world. Union Church proudly supports the college, its faculty, students, and staff, and seeks in whatever ways possible to nurture education, especially for those least able to afford it. We cooperate on many fronts and look forward to further decades of service together.

Today, Union Church continues its legacy of striving for social justice and peace for all. Members are instrumental in many peace and justice organizations, speak truth to those in power, march in peaceful protests for civil liberties, hold vigils for those killed in acts of violence and terrorism, and work hard to educate all citizens in the issues of the day, encouraging all to vote, work, and serve as if love demands it.